On the Art of Science

“Can you hear the music?”

—Niels Bohr in Oppenheimer (2023)

De Arte Scientiae

In academia (I can only speak to Physics), we admire the erudite to an extent. Namely, if their interests extend beyond the discipline without the promise of interdisciplinarity, then they are likely to become distracted from the discipline’s goals. Perhaps this is based on the feeling of how difficult doing science is—it is hard to imagine someone doing science at a high level while also enjoying the other aspects of life. We often talk of the long grueling hours, the sacrifices taken to achieve noteworthy results. I have heard some stories of this type, though not all, ending in great success; the fanatic undeniably gets results. They confirm our suspicion that you need to enter the struggle of science to do it well. But I don’t think this is the only way to be a good scientist.

Without pointing out that Einstein played the violin, those who do art benefit greatly for a number of reasons. Studying art can inform a creative process, which scientists can benefit from just as artists benefit from understanding their process. Furthermore, engaging in science like art as a form of human expression (Ars Scientiae) allows us to work in extralimital spaces: spaces beyond those that science and art individually inhabit but could potentially envelop both art and science.

Of course, I am biased—I want to do it all. I want to create music and perform science. I know that some of us feel emotionally starved when forced to do one thing and hate the idea of a life without both. Luckily, we are not alone. A mentor of mine, Dan Hooper, is an exceptional scientist who devotes his time to other pursuits, such as music and writing. I recall a conversation we had in my first year of graduate school. The conversation moved to a common sentiment—doing other pursuits in your junior career can kill it. One professor in the room shared his story of how he gave up performing music so that he could focus on his career. I struggled to make that specific choice; luckily there seemed to be an alternative. It was by Dan Hooper, who plainly told me that if I write 10 good papers per year, no one will be able to question my ability to do research.

When Dan was a postdoctoral fellow at Fermilab, he was writing his first novel and asked a senior scientist in his field to write the forward. This scientist told Dan that he would not write it and advised him to not publish the book as he thought the perception would ruin Dan’s career. It might have actually done so, except Dan mentioned that he had published 10 papers that year. The news more than easily convinced the scientist of the fidelity of Dan’s reputation and he wrote that forward! Since then, he has written several novels, hosted a successful podcast, and made his name as a local punk guitarist—all while being an incredibly accomplished scientist.

After he shared that story, it seemed to me that I just had to be exceptionally zealous in both science and art. To do both, no one should be able to question my ability to be productive in either. That’s very appealing to me—living two good lives is twice as compelling to me as one good life and gets me out of bed twice as quickly. However, it does seem a bit overzealous—I must admit that the idea of writing 10 good papers can be incredibly overwhelming to a young graduate student. But the sentiment was clear.

You might wonder how you can go about doing multiple things well, let alone just one well. Of course, I could go on about how there is plenty of time in the day if you work efficiently and I may share my personal points in the future. However, it is a topic that many people have written extensively about (i.e. Cal Newport, Ali Abdaal) and can be a distraction from actually doing the work at times. Instead, I’d like to offer how we can be better academics by studying art.

For the scientists looking for something tenable to take away from this, here are three things I have learned about doing science while writing music:

- How to go from idea to done.

- How to be kind to yourself.

- How science is an art.

1. Learn the creative writing process.

It is not immediately emphasized how writing scientific articles is an act of communication. A colleague once said, “Good science is good marketing”. What is good marketing? The study of communication often comes up in giving speeches, writing emails that people actually read, and designing high-traffic websites. This can intersect with art, where people often consider how media can affect a person emotionally. Lately, the conversation has emphasized how tech corporations use media that is effective at triggering the reward system, keeping people hooked on their apps. But art can do far more to people than cause brain rot. Art can inspire people to do incredible things, to believe the impossible, and to feel the inexplicable.

In the right hands, which is often not emphasized enough, art can make the abstruse clear. I want to emphasize that all creators, including the scientific ones, can benefit from studying the creative process. For instance, how authors write novels mirrors the development and finalization of new research projects. Scientists can gain much from learning how to make their ideas clear and relevant. How I compose large-scale symphonic works mirrors my research style. Studying communications and developing a creative process can help us better organize our ideas and make bold statements tactfully.

2. Recognize the graveyard of unrealized projects.

Good artists are great at failing.

Making music is hard. I think that writing orchestral, large-scale pieces is very hard. When one decides to start that, I find it hard to believe that their first true attempt is good. Doing research well is similar. Often, it is recommended that we jump into the pool not being able to swim—cited as the most efficient route by many though the dangers of drowning are pernicious and there is a survivorship bias. Understanding that the initial thrashing and failures are a part of the process is a life preserver. It is one that doing music and writing 100s of subpar unrealized works before writing the first good one taught me. It didn’t only teach me to be patient with myself but that those unrealized works are a crucial part of the learning process.

Failing is one of the best tools to learn, but only when we see failure as a teacher and use it to inform our understanding, rather than giving up and drowning. The graveyard is our growth and should not be feared, though it can often overwhelm us. When all our work ends up there, before we output works that we believe to be deserving of praise, it is hard to be emotionally steadfast. Doing art, to the scientist, can feel like a lower-stakes area to practice failure.

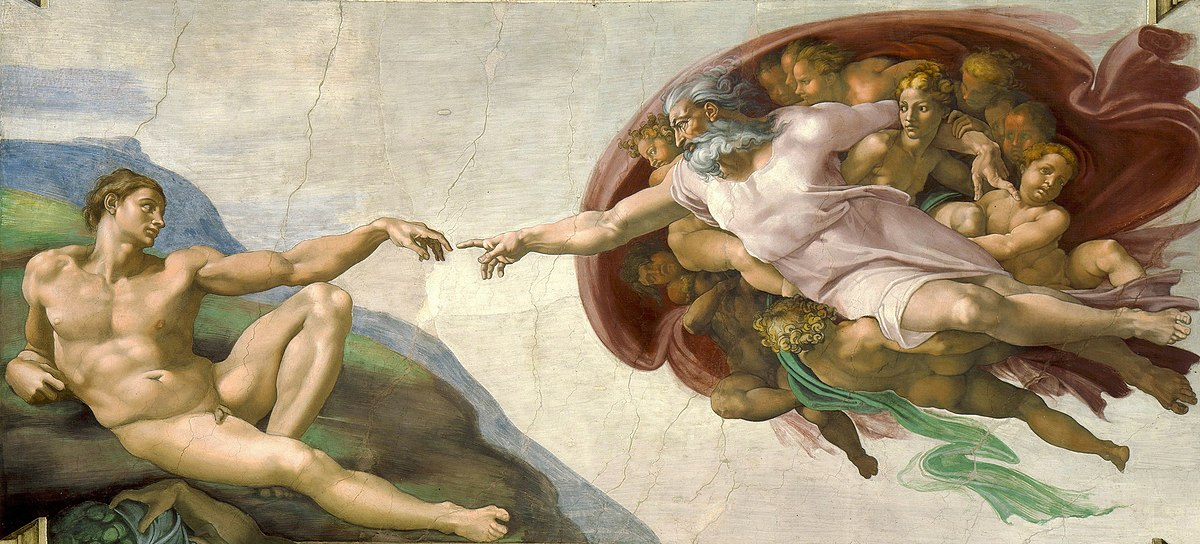

3. Place Science in the Humanities.

If we recognize science as an expression of human culture—our attempt to impose empirical tangibility on the intangible—then there is a level of aesthetic judgment in posing reasonable answers to interesting questions. Science as an art implies there is a taste that a scientist possesses like an artist, developed after having extensively engaged in this form of expression. Similar tastes coalesce with similar schools of thought, sharing similar aesthetic judgments. Not all questions are interesting to all scientific communities; it is worth studying why. For instance, many experimental physicists are disinterested in string theory since there are no obvious means of testing it, thus not being aesthetic. However, many theoretical physicists find string theory incredibly informative and thus highly aesthetic. Somehow, they both live under the same roof and work together on projects.

Of course, some questions are especially interesting, piquing a wide variety of people’s interests. Some answers are beautiful, elucidating far more than initially intended. These are the ones that we early career scientists can gain notoriety via engagement. I think that finding an especially interesting question and posing a beautiful answer is an art. To find those questions and pose tasteful answers, scientists need to have developed a sense of artistry.

Take personal ownership of your science and study how it relates to other forms of inquiry. Take it further, listen across disciplines. The humanities are broad and deep; it’s easy to ignore their influence as a career scientist. I recommend all scientists consider how the humanities engage with questions. The sciences are often touted to be rich when they cross into other disciplines. Notably, people love to bring up nature-inspired technology. This is of course very true and direct but art has also moved scientists to create things—art blatantly inspires. Inspiration can enable curiosity, so the scientist should be at least motivated by a sense of self-industry to study the arts and humanities. However, I imagine there is more to it in the extralimital spaces and how we inhabit them, which I hope to cover in the future. Consume science as you consume art and develop an aesthetic taste from your studies.

There are clear benefits scientists can have from studying art, from learning how to engage in an organized creative process to taking personal ownership of scientific judgments. Now, I ponder how the two might not be so different. It is not obvious to me how I can derive science from art, but I sense that there lies an esoteric magic that I might one day appreciate. Perhaps I am onto something deep about the scientific economy of ideas. Or perhaps I am just a distracted graduate student. Why not both? I choose to embrace widening knowledge through varied passions. Choose to find the knowledge in science and the humanities—learn from what exists around them. There lies the music.

And hey, if you've gotten this far, you're probably interested in what I have to say. So you might as well subscribe to stay up to date!

—Gio